How fallen Tanzanian president was lionised by African elites for doing exactly what they always protest against

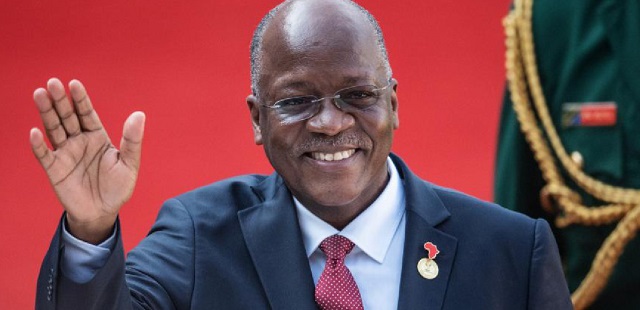

THE LAST WORD | ANDREW M. MWENDA | Since his death, former Tanzanian President John Pombe Magufuli has been an object of much praise from many commentators, including a large number Tanzanians. While I admired his motivations and intentions, I never agreed with Magufuli’s approach to reform. I was repulsed by the personalised and arbitrary way in which he conducted public affairs.

I am always puzzled by a large section of African elites. In one second they argue that power should be institutionalised and not personalised and in another; when a leader does what is emotionally satisfying to them but in a personalised fashion running roughshod over institutions, they cheer him along. They claim to oppose dictatorship and insist that power must be checked and balanced. Yet when a leader emerges who does what they demand but does it using arbitrary power, they support him. That was the love affair between Magufuli and this section of African elites.

Magulufi’s presidency was the ultimate manifestation of both the crisis and the contradictions of our elites. Upon coming to power, he exercised a degree of arbitrariness only reminiscent of Idi Amin. He would enter a government facility; be it hospital or school, and finding things gone wrong and without first establishing the circumstances under which disorder grew, he would – on impulse – fire the entire management. At a whim and in a heat of anger, he would cancel government contracts, fire government officials and reverse decisions by his predecessor.

But first a clarification: I am not against the use of a strong authoritarian hand to correct distortions created over decades. Indeed, I believe that reforming a deeply entrenched corrupt system requires a leader to exercise power without being hamstrung by unnecessary checks and balances. Attempts to uphold the highest standards of due process are more likely to abort reform. This is because entrenched interests can use the procedures of government, which they are adept at, to block reform. So, forceful action is a necessary precondition for effective reform.

However, there is a difference between forcefulness and arbitrariness, between institutionalised power and personalised highhandedness and between being authoritarian and being a village tyrant. I am not sorry to say Magufuli represented the latter. His were not reforms but emotionally charged and erratic personal interventions. All too often, he destroyed whatever was there without replacing it.

Reform cannot be based on emotions. It must be based on facts. It must be done systematically through some institutionalised process, not personalised to one’s feelings, acting in the heat of the moment. Even in medieval times, people did not govern without any recourse to established norms or procedures. It is possible that in his many reckless decisions, Magufuli may have corrected some mistakes. But even then, his emotionally charged and highly personalised arbitrariness cannot be justified by such accidental success.

I have seen reform elsewhere which has worked. One example is post 1986 Uganda; the other, post 1994 Rwanda. In 1the 990s, President Yoweri Museveni carried out far-reaching reforms. He knew what he wanted. But he used institutions such as the Army Council, the Army High Command, the National Resistance Council and cabinet to make critical decisions such as the return of Asian properties, return of ebyaffe, privatisation, civil service retrenchment, etc. His reforms were successful and have been sustainable because doing them through institutions gave them a collective mandate and therefore some degree of legitimacy.

The post The paradox Magufuli’s presidency appeared first on The Independent Uganda:.

from The Independent Uganda: https://ift.tt/3ufzGoj

0 Comments