Benefits and dangers of steam inhalation therapy

| THE INDEPENDENT | As Uganda battles a brutal second wave of the acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the agent that causes the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), there is still no effective antiviral treatment for the infection.

Instead, non-pharmaceutical preventive interventions remain the order of the day. The main ones include wearing masks in public, social distancing, and regular handwashing and sanitising.

In case of infection, however, one of the increasingly favoured interventions for alleviating symptoms is steam inhalation. But is it really effective and safe?

In an attempt to answer that questions, Dr. Ananya Mandal, an Associate Professor of clinical pharmacology at a Government Medical College in West Bengal, conducted some experiments.

She and her team did a small single-center study involving 10 asymptomatic healthcare professionals and those with mild COVID-19 symptoms. All 10 individuals had tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 via real-time polymerase chain reaction reverse transcription (RT-PCR) tests. The average age of the physicians and nurses was 44.4 years.

The patients were administered humidified steam through inhalation for at least 20 minutes (5 cycles of 4 minutes) within 1 hour for at least 4 consecutive days. Their airway mucosal membranes were exposed to the steam. The temperature of the steam was maintained at 55 and 65 °C in the first 4 to 5 min after the initiation of water boiling. The patient had a towel draped over the head and back, lowering toward the hot steam down to about 25 to 30 cm from the water.

At 24 hours after each cycle of treatment, viral shedding was measured by RT-PCR after collecting swabs from the nose and pharynx (rhino pharyngeal swabs). Viral load was measured using at least 6 Cycle Threshold Values.

Three participants dropped out of the intervention; 1 due to allergy, 1 started on hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin treatment since day 1, and 1 manifested more than three symptoms, which were moderate to severe.

Overall results were as follows: 6 patients with symptoms reported clinical improvement at the end of the intervention, 2 patients showed persistent symptoms of loss of smell and taste, 1 patient complained of persisting muscle pain and nasal congestion, all 7 patients tested negative after the first day of steam inhalation on four consecutive swab samples, and all 7 remained low viral shedders 3 to 5 days after following the protocol.

The allergic patient who had stopped the study on day 5 had showed a negative swab on inhalation on day 1. They showed a weak positive 3 days later. An additional swab on day 10 showed negative. The patient that had also started on hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin (for 9 days and 3 days, respectively) continued the steam inhalation till day 5 when their swab tested negative. The third dropped out patient with moderate to severe symptoms continued the steam inhalation protocol tested negative on swabs on days 8, 9 and 10.

Conclusions and implications of this study are that, although a small one, it shows the beneficial effects of steam inhalation in reducing viral shedding from infected patients. The team writes that this could be an “easily accessible, non-invasive and inexpensive procedure” which has been proven to be effective.

Early on in the virus’s outbreak, it was found that soapy water could help break down the viral envelope and thus denature it. Researchers have also added that heat can also lead to loss of infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Temperatures of 56 °C for 30 minutes in liquid environments are enough to breakdown SARS-CoV-2, the researchers say.

Steam inhalation cycles are thus considered to be useful in damaging the SARS-CoV-2 envelope and prevent infection, write the researchers. They write that the European Pharmacopoeia VI edition has recommended steam inhalations as a procedure to treat respiratory diseases.

Bigger trials needed

But the team recommended that steam inhalation should be subjected to larger clinical trials.

“Should our preliminary observations be confirmed, the protocol could be used against COVID19 or other viral infections using vapotherm masks, where temperature, time of exposure and size of steam particles can be set and monitored,” they wrote in November 2020.

Since then, a post shared hundreds of times on social media from South Africa has claimed that inhaling steam from a tea made from guava leaves, eucalyptus and an artemisia variety known as mhlonyane will “kill” the virus that causes Covid-19.

“This is false,” says the World Health Organisation (WHO). In fact, WHO does not recommend steam inhalation to treat or prevent Covid-19.

Different versions of the claim that steam inhalation can help prevent or treat Covid-19 have been circulating since the start of the pandemic in December 2019.

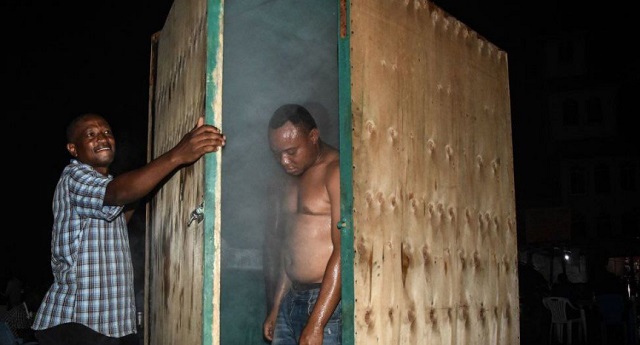

Since the second wave struck Uganda recently, steam inhalation has become a go-to fad for prevention and treatment of COVID-19. In some cases, it has been promoted by healthcare providers.

It is all part of a panic reaction prompted by the government’s reversal of some of earlier lifted restrictions on some businesses and gatherings as COVID-19 infections and deaths spiked.

The government has send pupils back home from school and imposing a partial geographical lockdown.

However, experts say there is no scientific evidence to support the claims that steam inhalation cures COVID-19.

The post Steaming against COVID-19 appeared first on The Independent Uganda:.

from The Independent Uganda: https://ift.tt/3gomCbN

0 Comments