Doctors suggest HIV-like treatment approach

Scientists have found evidence of a resistant form of malaria in Uganda, a worrying sign that the top drug used against the parasitic disease could ultimately be rendered useless without more action to stop its spread.

Doctors suggested that instead of the standard approach, where one or two other drugs are used in combination with artemisinin, doctors should now use three, as is often done in treating tuberculosis and HIV.

Researchers in Uganda analysed blood samples from patients treated with artemisinin, the primary medicine used for malaria in Africa in combination with other drugs. They found that by 2019, nearly 20 percent of the samples had genetic mutations suggesting the treatment was ineffective. Lab tests showed it took much longer for those patients to get rid of the parasites that cause malaria.

Drug-resistant forms of malaria were previously detected in Asia, and health officials have been nervously watching for any signs in Africa, which accounts for more than 90% of the world’s malaria cases. Some isolated drug-resistant strains of malaria have previously been seen in Rwanda.

“Our findings suggest a potential risk of cross-border spread across Africa,” the researchers wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine, which published the study on Sept.22.

The drug-resistant strains emerged in Uganda rather than being imported from elsewhere, they reported. They examined 240 blood samples over three years.

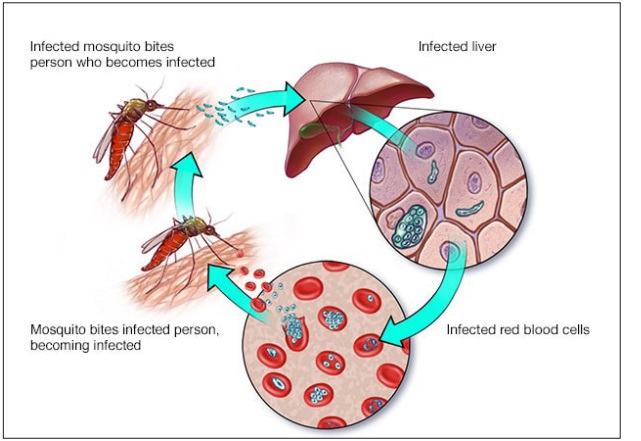

Malaria is spread by mosquito bites and kills more than 400,000 people globally every year, mostly children under 5 and pregnant women.

Dr. Philip Rosenthal, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, said that the new findings in Uganda, after past results in Rwanda, “prove that resistance really now has a foothold in Africa.”

Rosenthal, who was not involved in the new study, said it was likely there was undetected drug resistance elsewhere on the continent. He said drug-resistant versions of malaria emerged in Cambodia years ago and have now spread across Asia. He predicted a similar path for the disease in Africa, with deadlier consequences given the burden of malaria on the continent.

Dr. Nicholas White, a professor of tropical medicine at Mahidol University in Bangkok, described the new paper’s conclusions about emerging malaria resistance as “unequivocal.”

“We basically rely on one drug for malaria and now it’s been hobbled,” said White, who also wrote an accompanying editorial in the journal.

He suggested that instead of the standard approach, where one or two other drugs are used in combination with artemisinin, doctors should now use three, as is often done in treating tuberculosis and HIV.

White said public health officials need to act to stem drug-resistant malaria, by beefing up surveillance and supporting research into new drugs, among other measures.

“We shouldn’t wait until the fire is burning to do something, but that is not what generally happens in global health,” he said, citing the failures to stop the coronavirus pandemic as an example.

According to data from the Severe Malaria Observatory, Uganda has the 3rd highest global burden of malaria cases (5%) and the 8th highest level of deaths (3%). It also has the highest proportion of malaria cases in East and Southern Africa 23.7%. There is stable, perennial malaria transmission in 95 percent of the country.

According to the latest data from the Weekly Malaria Status Report of the Ministry of Health Knowledge Management Portal, there were 129,829 malaria confirmed cases reported in Week 34 (August 23-29, 2021);, a decrease by 2% from 132,430 the week before. The test positivity rate for the week was 50.2% compared to 49.9% the week before.

The highest Test positivity rates were reported in Nabilatuk (81.7%), Alebtong (73.3%), Kotido (72.4%), Yumbe (72.3%), Butebo (72.0%) and Abim (70.1%).

There were 21 malaria deaths in the week compared to 22 malaria deaths in the previous week. Butaleja (1), Iganga (1), Kabale (1), Kampala (1), Kamwenge (1), Kanungu (1), Kikuube (1), Kitgum (2), Lamwo (1), Mbale (5), Nebbi (1), and Yumbe (4)

Uganda is implementing a new Malaria Reduction and Elimination Strategic Plan 2021-2025 that aims to reduce malaria infections by 50 percent, morbidity by 50 percent and mortality by 75 percent by 2025.

The Plan is the result of coordinated efforts between the National Malaria Control Division (NMCD), the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), the World Health Organisation (WHO), the Global Fund, and other strategic partners. It aims to achieve these goals through stratification to ensure appropriate tailoring of intervention mixes for the various epidemiologic contexts, universal coverage of services (including in the private sector), robust data management and social behavioral change, multisectoral collaboration, and malaria elimination in two districts.

The National Malaria Control Division is currently revising the malaria case management guidelines on Artemether-lumefantrine (AL) as a well-tolerated drug during the first trimester, discarding monotherapies of artemether or Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), and recommendations on the correct artesunate dosing relative to age and weight. There is also agreement to conduct malaria death audits and implement Integrated Community Case Management (iCCM) in hard-to-each areas.

****

The post Malaria strain resistant to drugs found in Uganda appeared first on The Independent Uganda:.

from The Independent Uganda: https://ift.tt/2Wzf9zO

0 Comments