Why the soldiers want change

Kampala, Uganda | THE INDEPENDENT | Military coups and attempted putsches are on the increase on the African continent. And the leaders of African states are nervous.

At their latest summit of the African Union (AU) heads of state and government in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, many of them spoke out strongly against military takeovers. The leaders were speaking after one successful military coup and another failed one in just one week; in Burkina Faso on Jan.24 and Guinea Bissau on Feb.01 respectively.

Addressing African foreign ministers ahead of the summit, Moussa Faki Mahamat, chair of the AU Commission, denounced a “worrying resurgence” of such military coups.

An unprecedented number of member states have been suspended from the bloc as a result of the military power grabs. In January, Burkina Faso joined Guinea, Mali and Sudan in being shut out from the AU, after soldiers in Ouagadougou toppled President Roch Marc Christian Kabore.

“Every African leader in the assembly has condemned unequivocally… the wave of unconstitutional changes of government,” Bankole Adeoye, head of the AU’s Peace and Security Council, told journalists, “Do your research: At no time in the history of the AU have we had four countries in one calendar year, in 12 months, been suspended.”

Following the failed takeover in Guinea-Bissau, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) summoned a one-day emergency meeting to discuss what its chairman, Ghana’s President Nana Akufo-Addo, described as a “dangerous trend” in the sub-region. Both ECOWAS and the AU had condemned the coup in Burkina Faso and, before that, last year’s successful military takeovers in Mali and Guinea.

But according to Ebenezer Obadare, a commentator in the Africa in Transition magazine of the Council on Foreign Relations, “it goes without saying that the continent’s leaders are motivated by self-reservation”

He adds: “Most—especially in West and East Africa—face challenges not unlike the countries which have succumbed to military rule, including continued failure to contain a festering Islamist insurgency, restlessness within the armed forces, political corruption, and popular disaffection with the slow pace of economic reforms. This makes their fear of the coup contagion spreading to their respective national barracks understandable”.

He says coup leaders tap into the dissatisfaction and quotes leader of the Guinean junta Mamady Doumbouya.

Doumbouya said: “If the people are crushed by their elites, it is up to the army to give the people their freedom, the duty of a soldier is to save the country. We will no longer entrust politics to one man. We will entrust it to the people.”

Doumbouya said: “If the people are crushed by their elites, it is up to the army to give the people their freedom, the duty of a soldier is to save the country. We will no longer entrust politics to one man. We will entrust it to the people.”

Obadare also notes a generational conflict behind the coup. The coup leaders such as Mamady Dombouya, Assimi Goita, and Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba are forty-one, thirty-nine, and forty-one respectively. Chad’s Mahamat Idriss Deby, who technically did not plan a coup but inherited the mantle of leadership under controversial circumstances following his father’s death in April 2021 is, at thirty-eight, the youngest.

They all received their military training in the West, suggesting an exposure not only similar to strategic philosophies, but also ideas about politics and the political process.

A generational perspective gains further credence when one considers the ages and time in office of the leaders they displaced. The older Deby, sixty-eight at the time of his death, had been in power since December 1990, Guinea’s Conde was 83 and Mali’s Ibrahim Boubacar Keita died last month aged 76. The recently deposed Kabore is 64.

“This is not the first time that a young generation of African military men have stormed into office on the back of assurances of a quick shot in the arm for the economy and an even quicker return to democracy,” he says.

He points at Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni who was 42 when he seized power in 1986. Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, 79 this year, has been in power since 1979 when he took office aged 43. Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, 64 this year, was 43 when he mounted the saddle in 2000.

Obadare cites a 2019 survey of African military professionals by the Department of Defense’s Africa Center for Strategic Studies which found that 46% viewed corruption as their greatest security challenge. They said corruption starves soldiers of the resources needed to carry out their constitutional duties and, in the long run, it delegitimises the armed forces by depriving them of their “professional swagger”.

“Outside the barracks, young people facing increasingly constricted horizons agree with their military counterparts on corruption and political fossilization,” he says.

More coups succeeding

The surge in coups and attempted coups began in 2019. That year saw one successful military coup and two failed attempts. It started in Gabon, West Africa. On January 07, 2019 soldiers led by Lt. Kelly Ondo Obiang attempted to topple President Ali Bongo Ondimba but failed. On April 10, 2019, Sudanese soldiers, led by the former First Vice President Lt. Gen. Ahmed Awad Ibn Auf attacked the presidential palace and overthrew President Omar al-Bashir. Then on June 22, 2019, Ethiopian soldiers led by Brig. Gen. Asaminew Tsige attempted and failed to overthrow Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

The following year, 2020, saw one successful military coup and one failed attempt. On August 18, 2020, Malian soldiers led by Col. Assimi Goïta seized President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta and Prime Minister Boubou Cisséand overthrew the government. But Central African Republic rebels led by Ex-president François Bozizé who attacked the capital Bangui on December 17, 2020 failed in their attempt to topple President Faustin-Archange Touadéra.

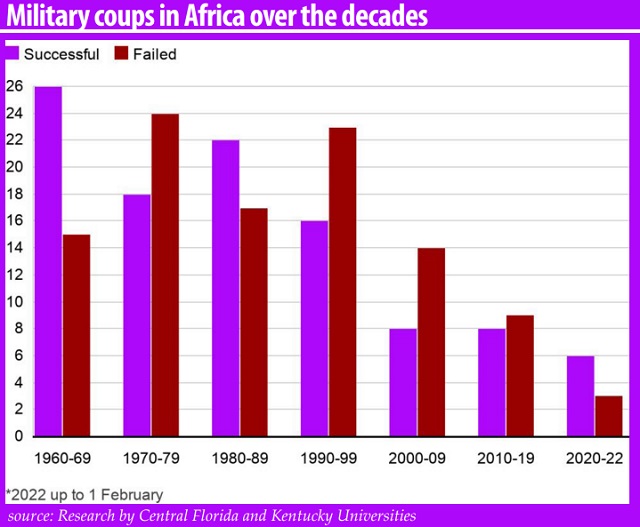

In a sign of an emerging dangerous trend, last year there were at least three successful coups and two failed attempts. It was also the first year in the history of coups in Africa where the number of military coups that succeeded exceeded the number of those failed. Until last year, Africa had witnessed more failed coup attempts that successful coups.

The year started with a military takeover of government in Guinea on September 05, 2021. Soldiers led by Col. Mamady Doumbouya kicked out President Alpha Condé. A few days later, on September 21, 2021, there was an attempted coup in Sudan which failed. But another attempt on October 25 was successful and Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan kicked out the civilian government of Prime Minister Burhan Abdalla Hamdok.

For some observers, the recent surge in military coups and coup attempts takes the politics on the African continent many steps backwards to the immediate post-independence era of the 1960s and 70s. In the period, Africa had about four coup attempts each year. Some succeeded but many failed. The number of coups had declined dramatically to about two per year since the 2000s until now. Last year, 2021, saw six coups or attempted coups recorded.

In September 2021, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres voiced concern that “military coups are back,” and blamed a lack of unity amongst the international community in response to military interventions.

“Geo-political divisions are undermining international co-operation and… a sense of impunity is taking hold,” he said.

Judd Devermont from the US-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, believes a “lenient” approach by regional and international bodies “has enabled coup leaders to make minimal concessions while preparing for longer stays in power”.

Ndubuisi Christian Ani from the University of KwaZulu-Natal says popular uprisings against long-serving dictators have provided an opportunity for the return of coups in Africa.

“While popular uprisings are legitimate and people-led, its success is often determined by the decision taken by the military,” he says, “African countries have had conditions common for coups, like poverty and poor economic performance. When a country has one coup, that’s often a harbinger of more coups.”

Of the 13 coups recorded globally since 2017, all but one – Myanmar in February 2021 – have been in Africa.

Undermining democracy

According to scholars Leonard Mbulle-Nziege (research analyst at Africa Risk Consulting ) and Nic Cheeseman (professor of democracy at the University of Birmingham in the UK), the problem of military coups emerges when supposedly democratic leaders start to use undemocratic strategies to keep themselves in power against the wishes of their people. Such leaders atrophy support because they undermine their own democratic credentials in a context of rising instability.

In Guinea, former President Alpha Condé controversially modified the constitution in 2020 to allow him to run for a third term in office. This was an unpopular strategy, particularly because neither the constitutional referendum nor the general election that he subsequently won were free and fair. Condé had also become increasingly authoritarian in the months leading up to the coup, jailing and exacting violence against his political opponents and anti-government activists.

According to commentary on the BBC, former Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta similarly was accused of rigging the 2020 legislative elections. In addition to concerns over growing corruption and rising insecurity, this undermined his personal legitimacy.

****

The post Military coup fear mounts appeared first on The Independent Uganda:.

from The Independent Uganda: https://ift.tt/9vTriBD

0 Comments